Tomorrow (Jan 16th 2022) I’ll be speaking at the free virtual conference PancakesCon 3 on “Structuring Intelligence Assessments and Gin Cocktails.” The conference’s format is to introduce material to students or new folks to a topic in the first half of the presentation and in the second half do something completely not work related, my second half will be non-intimidating and easy yet delicious to make gin cocktails (normally I’m more of a bourbon/rye guy but when it comes to cocktails I’m a gin fanatic).

As a result I decided to sit down today and write about the first half of my talk while practicing the second half of the talk. Therefore this blog will likely be more musings and recommendations than wildly coherent and well written thoughts. The talk is only 15 min long so I want to condense as much as possible into that timeframe and map the blog accordingly.

If this blog gets your insights going and you find the topic fun you can check out my SANS FOR578 – Cyber Threat Intelligence class where we talk about these topics and more. I’ll also include some reading materials and references at the end of the blog as well. Unfortunately and fortunately this one topic could (and has throughout history) been a complete manuscript/book but I’ll try to give me abbreviated version on the topic.

First Key Point

There’s a lot of opinions as it relates to cyber threat intelligence. I often semi-joke that the only thing Analyst 1 and Analyst 2 can agree on is that Analyst 3 is wrong. Intelligence doesn’t specialize in the area of facts. If everything was a fact or a simple yes or no answer you likely wouldn’t need intelligence analysts. Intelligence analysts specialize in going into the unknown, synthesizing the available information, and coming up with an analytical judgement often requiring you to go beyond the evidence (an analytical leap). There are some things you shouldn’t do, but generally speaking my retort to people is: “you do you.” There is no one right or wrong answer. I’ll give you my thoughts around intelligence assessments in this blog to help you but it should not be construed as the only answer. It is simply a consideration built on experience. The first rule of cyber threat intelligence, to me, is that if you’re being an honest broker then so long as you’re satisfying the requirement of your customer then everyone else’s opinion is irrelevant. Or said differently: everyone’s a critic, if you are delivering intelligence to the best of your ability to a consumer against their requirement and your intelligence helps them achieve their outcome then all the nit picking in the world about how you got there is irrelevant to me. Key focus on honest though. We deal in the world of trust because a lot of what cyber threat intelligence analysts do looks like magic to those not in our field. If you betray that trust, especially on topics that people aren’t well versed in and thus need to rely on trust more, then just pack up your bags and go home – you’re done. (As an aside that’s why I hate those stupid cyber attack pew pew maps so much. I don’t care how useful they are to your budget or not – it’s dishonest. The visualization is pointless and if a consumer digs a layer deeper and finds out it’s just for show then you come off as someone that is willing to mislead them for a good outcome. I.e. you lose trust).

Being Precise In Word Usage

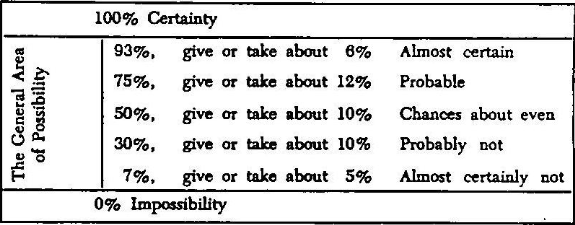

Much has been written about intelligence assessments. One of the required readings is by Sherman Kent from 1981 at the Central Intelligence Agency titled “Words of Estimative Probability”. One of the beautiful things that Kent puts forward is the necessity to be measured and consistent in what we do. I.e. it’s not paramount to pick one direction over another but it is paramount to be transparent and repeatable in what direction you chose and consistent in its application. If you decide that you like the word “even chance” then you should know what that means to you (50/50 probability subjectively but as appropriately applied as you can) and consistently use that language in those scenario. You are more than welcome to use other people’s standards (like Kent’s) or create your own. It’s likely better to use what exists, but if you need to adapt or create your own you can just make sure it’s something you can make available to your team and consumers so its transparent and has definable meaning. I would recommend creating a style guide for you/your team and defining the words you do and do not want to use and as much as possible tying it to a number to help them understand how those words relate to each other. Defining words you do not use is also helpful. As an example, I cannot stand the word “believe” in intelligence assessments. As my friend Sergio Caltagirone would say belief is for religion not intelligence.

Figure 1: Example from Kent’s Words of Estimative Probability

One of the most important things intelligence analysts can do is reduce the barriers and friction between a consumer consuming the intelligence and leveraging it. Write briefly. Don’t use more words than required to make the point. Remove ambiguity wherever possible. In this topic, to convey what we do and don’t know as quickly as possible but in such a way that doesn’t require the consumer to learn our language over and over. The consumer should be familiar over time with the language we use and what it means to help inform them how and when they can leverage it against their requirement.

In a perfect world I want intelligence reports to be subjected to the Pepsi Challenge. I should be able to remove the logos, branding, color schema, etc. off of your intelligence product/report and put it in front of a consumer that you deal with and place it randomly next to other teams’ intelligence reports. The consumer should be able to pick out which report is yours. Language consistency, structure of the report, where the assessments are, where the suggested actions are, etc. all play into that.

Following that logic then our intelligence assessments should also be as consistent as possible.

Intelligence Assessments

If something is a yes or no answer then it is a factual statement. “Was this malware on this system?” can be answered as a yes or no question because the malware is either there or not and it is something we can prove. There should not be intelligence assessments for factual statements even if the factual statement is part of the threat intelligence. I.e. I would not expect to see someone say “We assess with moderate confidence the malware is on that system.” You can go and prove it or you cannot, but it’s not an assessment. The world of intelligence is for one step beyond the evidence. It’s the analysis and synthesis of the data and information to create new insights. However, we might say something like “We assess with low confidence, given the presence of the malware on the system, that our company is a target of their operation.” We do not know for sure whether or not the adversary intended to target us or if we were just a random victim. We can synthesize the available information and make an assessment based on our experience and what we’re seeing to reach an intelligence assessment.

I see most organizations leveraging Kent’s estimative language (or something close to it) in their wording and then using the estimative language you’d find in government intelligence agencies. Typically that is:

- Low Confidence

- Moderate Confidence

- High Confidence

You can create middle grounds like Low-Moderate or Moderate-High but I try to avoid that myself as it often is more confusing to the consumer. Keeping it to three confidence levels in your intelligence assessment and having some rules you set out for yourself and your team on what that means often suffices.

General Rules for Confidence Levels

Again, you do you. But for me I like to generally follow the following guidance as it relates to designating confidence levels. Also I do think there’s a difference in cyber threat intelligence vs. the intelligence you might be delivering to the President of the United States to go to war. But these generally hold.

- Low Confidence: A hypothesis that is supported with available information. The information is likely single sourced and there are known collection/information gaps. However, this is a good assessment that is supported. It may not be finished intelligence though and may not be appropriate to be the only factor in making a decision.

- Moderate Confidence: A hypothesis that is supported with multiple pieces of available information and collection gaps are significantly reduced. The information may still be single sourced but there’s multiple pieces of data or information supporting this hypothesis. We have accounted for the collection/information gaps even if we haven’t been able to address all of them.

- High Confidence: A hypothesis is supported by a predominant amount of the available data and information, it is supported through multiple sources, and the risk of collection gaps are all but eliminated. High confidence assessments are almost never single sourced. There will likely always be a collection gap even if we do not know what it is but we have accounted for everything possible and reduced the risk of that collection gap; i.e. even if we cannot get collection/information in a certain area it’s all but certain to not change the outcome of the assessment.

For purposes of clarification, the topic of “single sourced” to me relates to where we are getting the information. As an example, if you are operating only on netflow or malware repositories like VirusTotal it is highly unlikely you will get to a high confidence assessment out of any one of those. It is possible that you have commercial access to netflow, and malware repositories, and you have information shared from 3rd parties that help you get to a high confidence assessment. In a perfect world you’d have non-intrusion related information as well depending on the assessment. (e.g. you’re trying to attribute an operation to a specific government or government agency I’d prefer to see you have a lot of different types of 1st party data as well as 2nd or 3rd party data supporting the assessment and in an ideal scenario have more than just intrusion data. This is an area I often conflict with the private sector intelligence reporting; while I am a huge fan of private sector intelligence and think it runs circles around some types of government intelligence I generally hold a higher standard for confidence assessments on the topic of attribution than I see represented in *some* public reporting. That’s not a knock on every team out there – but I see “high confidence” for attribution thrown out quite a bit for data that just came out of an incident response case or malware repositories and you really need a lot more than that in my opinion).

Collection/Information gaps are anywhere there’s useful information or data that you don’t have access to. As an example, if an adversary targets an electric power plant I may have access to their malware but maybe I don’t have the initial infection vector. The missing data/information on the initial infection vector would be a collection gap. Additionally, maybe I see what their command and control server is but do not have access to what’s on the command and control server, who is accessing it when, etc. and those would be collection gaps. Some collection gaps you can solve for, some you cannot. But you must think through as many of them as possible and what that might mean to the assessment.

Structure of an Assessment

Again it really depends on you and your use-cases but generally speaking I like intelligence assessments’ structure to also be consistent and follow a repeatable and understandable pattern.

I often like my assessments to follow the following pattern:

Confidence + Analysis + Evidence + Sources

As an example:

“We assess with moderate confidence that ELECTRUM is targeting the Ukrainian electric sector based on intrusions observed at the Kyiv electric transmission substation by our incident response team as well as publicly available data from the Ukrainian SSU.”

The depth you go into analysis, evidence, and sources will vary entirely based on what your consumer needs and finds relevant.

Everyone Loves to be High

One of the big flaws I see in cyber threat intelligence teams is a well intentioned but misplaced effort to have as many assessments as possible be High Confidence. Your consumer may expect high confidence assessments. You may have accidentally trained them to expect that those are the ones to operate off of. But in reality, a low confidence assessment is a perfectly valid and well supported assessment. If you aren’t able to make an assessment with confidence levels its perfectly fine to say something to the effect of “We haven’t assessed the situation yet but here is my analytical judgement based on my experience and the available information.” In other words not everything needs to be an intelligence assessment.

But if you do give an intelligence assessment you need to train your consumer to understand that all three levels are appropriate to use. A low confidence assessment is a good assessment someone can have confidence in. Often times, the difference between a Low Confidence assessment and a High Confidence assessment comes down to time and sourcing. Do I have the time and collection to get to that level of confidence or not? While I love giving consumer’s Low Confidence assessments its perfectly reasonable to offer them what it would take to get to a higher level if they really need it: “If we had X more time and Y more resources we likely could raise the confidence level of our assessment or find an alternative assessment.” Be careful in how you use that but I generally find being transparent with consumers to empower them to make better decisions is almost always a good thing.

If we accept that low confidence assessments are good assessments. And we accept that to get to a Moderate or High level generally requires more time and resources. Then if were to look at all the assessments an intelligence team produces across a given time period (e.g. quarterly or annually) would fall into an inverted pyramid pattern.

Figure 2: Rob Makes a Pyramid in PowerPoint After Drinking Lots of Gin

I would expect to find that roughly 40-60% of the assessments produced by the team are Low Confidence Assessments. I would expect 20-30% are Moderate Confidence. I would expect 10-20% are High Confidence. That’s a general rule of thumb; many variables will impact that including the needs of the consumers. But generally speaking if I am trying to only release Moderate and High Confidence assessments the impact to my consumers is usually requiring more time and resources than necessary if they are comfortable making a decision on Low Confidence assessments. If the consumer truly requires a higher level of confidence – no problem! But if they don’t require that then don’t put barriers in between them and the intelligence they need to make a decision.

“But Rob my boss really only listens if we have High Confidence assessments.” I hear this often with my FOR578 students. You need to sit your consumer down then and have a conversation about this and how they can leverage your lower confidence assessments. You can try to pull historical information on your assessments vs. the decisions made and try to showcase that Low Confidence assessments are good assessments, they have a role. There’s tips/tricks here for this but it’s not really the point of the blog and I’ll just note that we serve as the request of the consumers (intelligence does not exist for intelligence’s purposes) but we want to make sure to arm them with the best information possible for their decision making process. Sometimes that does include correcting them.

Closing Thoughts

As mentioned this isn’t meant to be a doctoral thesis on the topic. This is largely just a resource for the people at my talk tomorrow and hopefully useful to others as well. However, there’s a lot of resources out there (some referenced in this blog) to give you help. Here’s some of my favorite as it relates to this topic:

The Cycle of Cyber Threat Intelligence

Presented by one of my awesome friends/peers/FOR578 instructors Katie Nickels where she highlights some of the FOR578 material in a masterful way to condense the view of cyber threat intelligence to folks in an hour webinar.

Hack the Reader: Writing Effective Threat Reports

Presented by Lenny Zeltzer this is a great conference talk on threat reports that also touches on formatting (don’t roll your eyes, reduce friction for your consumers its part of the job)

Pen-to-Paper and the Finished Report

Presented by Christian Paredes this is a mini master level class on dealing with tough questions and translating things into useable intelligence reports.

Threat Intel for Everyone: Writing Like a Journalist to Produce Clear, Concise Reports

Presented by Selena Larson who I had the privilege to work with for awhile at Dragos. I would highly recommend any intel team look at hiring journalists to the team at some point.

I Can Haz Requirements? Requirements and CTI Program Success

Presented by Michael Rea, at the end of the day everything ties to the requirement. Do not do intel for intel’s point. No one cares how smart you are or how much you learned. They care about you giving them information that meets their requirement so that they can achieve their goals/outcomes. This is a great talk on that point that wraps into assessments as well.

*Edit Jan 16th 2022*

By popular demand here is my excel spreadsheet for Gin cocktails for my PancakesCon talk. I’ve changed some of the recipes a bit for my own personal taste. Feel free to adapt.