After a lot of thought and consideration I decided to join the military again, this time in the Army National Guard. The Guard provides me the appropriate flexibility to be able to continue my roles as CEO of Dragos and SANS ICS Practice Director while getting to serve my country and community once again in uniform. In this blog post I want to inform the community of the decision answering as many questions to help those that care understand why.

The Blue Years

My first time in military service began when I graduated the United States Air Force Academy and became a 2nd Lieutenant in the United States Air Force. As an active duty Cyberwarfare Operations Officer I quickly got to work on my passion for industrial control systems (ICS) / operational technology (OT) while getting to serve with amazing people. Most of my time in the AF was spent at the National Security Agency where I was empowered to design and lead a first-of-its-kind mission identifying state actors targeting and compromising the ICS/OT of global critical infrastructure. It was there that I was surrounded by amazing military and civilian leaders of all types and ranks while being afforded the opportunity to pioneer a lot of amazing work. It was that work and those connections that would take me down a path to developing my SANS courses and eventually founding Dragos, Inc. As many have heard me say over the years I eventually decided to leave military service. As a Captain I was tasked to leave the NSA and return to big Air Force. The unit I went to was amazing but I found big Air Force lacking on the cyber topic, highly political, and ultimately dysfunctional on the topic of cyber though many great people and units existed accomplishing wonderful things in isolation. I left for numerous reasons including some disagreements on what doing cyber offense and its consequences meant to global civilian infrastructure but another major reason was watching my enlisted troops be treated as “cyber” meaning an exploit developer might be pushed to patch servers with no input from themselves because – all cyber is the same. We were losing a lot of people and there simply wasn’t any ability for me to help on the inside. I was proud of my service but knew when it was time to leave.

The Air Force provided me a lot and I was proud of my military service. I was most proud to serve with amazing Americans who believed in service before self. While I never regretted leaving there’s always been a part of me that missed the comradery and mission – though I quickly established a very similar culture at Dragos and have found that comradery and mission to be the best I’ve ever had and most fulfilling for me personally.

The Interim Years

Since leaving the AF I’ve arguably have done pretty well for myself and became fairly well known in the ICS/OT cybersecurity community. I love being the founder and CEO of Dragos; the nearly 500 employees we have are amazing human beings focused on the mission and protecting people. We truly live our values and our mission of safeguarding civilization. Not just the countries we live in (as a global company that is humbly quite a few) but everyone. I often tell people that every 35 year old mom deserves to go home to her 5 year old kid regardless of country or creed. We protect civilians, we protect people, and we protect them from really bad people. A few years ago Dragos became the first ever ICS/OT “unicorn” (company valued at north of 1B+ USD) and our software and services protect thousands of organizations. We have been on the front lines of almost every major ICS/OT cyber attack, routinely get called in to advise governments around the world, have uncovered numerous new ICS malware frameworks and threat groups, and are constantly sharing our expertise with the community freely to make it better. Our Community Defense Program even provides all of our software, our training through Dragos Academy, and membership in OT-CERT for free to any US or Canadian electric, water, or gas company under $100m in Revenue for free forever. If you look at the utility space that accounts for nearly 98% of all utilities in the US and Canada – and because of the partnership with our larger customers we’re able to do the mission – for free – for those that need it most – while building a business as well on principles that ensure we can be a 100+ year type company. Our people are simply amazing. Our community is amazing.

Most importantly, I have a beautiful wife and three sons. I spend a lot of time thinking about their future, what I will leave behind, and all the amazing people across the community and their families. I love my work at Dragos and have not been “wanting” for anything. I am financially sound and have been on every global stage of importance you can imagine from the White House to the World Economic Forum’s Davos conference and I keep getting pulled into conversations where I think I can help. While I am not flush with free time, I do not want to “leave anything on the court” when my eventual time to leave this life comes. I want to know I did everything I could to help our families and communities be safer.

Over the years there has been one single conversation that I keep getting pulled into by every level of government: what happens when conflict comes to the U.S. and our adversaries target ICS/OT across the country. What does that look like when our adversaries aren’t just trying to pre-position but instead try to hurt people. What is the governments role? What should we do?

I know Dragos will be involved. We will be on the front lines and have the expertise – arguably a lot more expertise and capability than that of the US government even on this topic. But the government has an important role and responsibility to play as well – and is it ready – is it ready locally – is it ready nationally?

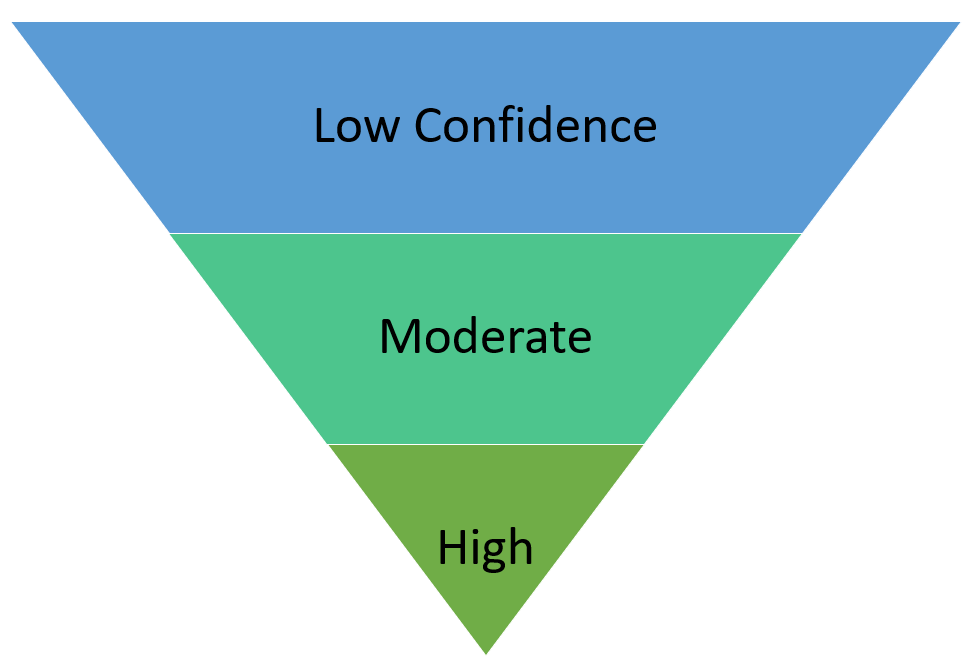

And time and time again regardless of the advise and amazing work by so many in there still isn’t a national response strategy, there isn’t a coordinated effort, and the people in the right places know we simply aren’t prepared. And yet, our adversaries are getting more sophisticated and bold at a time our industrial community is become more digital, connected, and homogenous. PIPEDREAM and VOLT TYPHOON/VOLTZITE have deeply concerned me over the last few years. I am not a war mongering, anyone who’s ever served in the military hate war more than anyone else can possibly imagine. I am not a fear mongering, I have spent most of my career killing hype not creating it. But I am concerned as the world become more geopolitically tense and complex and I am deeply worried about what is coming and where the current state of government is on this topic.

The Green Years

Last year I was involved in some pretty senior conversations with leaders across the US government. There was a sort of plea to find a way to come back into government service and help more fully. And while empathetic to the call I knew in my “blue years” that its rare that any single person can change the course of government. I was unsure if there was any reasonable path for me to actually help and not get burned out from the frustration. I also knew I could not leave Dragos – I love my mission there and it is an equally important part of this conversation and strategy. Then I met some folks who opened my eyes to a route through the National Guard. Where I could serve again in the military but with the appropriate balance to be able to still fully lead Dragos. Where I could serve not as an individual trying to move the mountain but as a part of an amazing group of people all trying to do the same thing. A team and a mandate. So I began the process mid 2024 not knowing what 2025 would bring and if I’d even be able to join (it’s not exactly an easy process).

Through a lot of sponsorship and support of others (MG Williams, BG McGuire, COL Mazur, LTC Garner, LTC Messare – thank you!) I was direct commissioned into the Army as a Lieutenant Colonel in Feb 2025 serving as part of the 91st Battalion in Virginia. I was told that I’m the first ever direct commission to the rank of LTC in cyber in the Army – but to be fair I only skipped 1 rank (Major) if you think of my Air Force service – I don’t think the Army counts the Air Force time though (said playfully). My current role is as the Executive Officer of the IOSC Battalion where I get to inherit the amazing work already done by the team on the exercise Cyber Fortress (seriously it’s impressive) and use it as part of the larger strategy. I don’t intend to detail everything in a public blog but the short of it is to establish a strategy for how the government responds to infrastructure attacks in partnership across government agencies and the private sector in Virginia using Cyber Fortress to demonstrate it and then work across government to take insights from all the other pockets-of-excellence that have formed on this topic and roll out a national strategy all while training our most powerful capability – our people – in how to prepare and respond to infrastructure attacks that threaten our citizens.

I am humbled to be the least interesting person in the 91st – they are without a doubt the best cyber unit in the military – and we’re going to put a dent on history together.

I am excited that the Army National Guard provides me the balance to serve my country in uniform while also being able to fully lead and be engaged at Dragos. The time commitment is not significant to the guard but it is impactful.

I encourage others to explore opportunities for similar service if the topic interests you. If they can be flexible enough and exciting enough to get me to join – you might be surprised what you find for yourself as well.

Thank you all for the ongoing support and love over the years – I am excited to get to try to “leave it all on the court” and I hope to not let anyone down.

I’ll detail some Frequently Asked Questions of sorts below, I’m sure there’s a few.

FAQs

Are you stepping down as CEO or changing your involvement at Dragos?

No, not at all. I have an amazing executive leadership team and built Dragos to be a scalable company. The National Guard also allows me to continue in my role and I am far from the first to do so – almost all of our troops have full time jobs in the civilian space which is exactly the model – combine the best of civilian and military expertise to be able to provide a unique combination to the community. As word got out about me joining there have already been a bunch of rumors that competitors or anti-bodies in the community spread. I heard one recently that I was stepping down as CEO and enlisting in the AF. Wrong and wrong. To parrot a famous quote – the rumors of my demise have been greatly exaggerated.

Are you worried about conflicts of interest being in OT cybersecurity in civilian and military capacities?

No. The Guard exists to make sure civilian and military expertise can align and the country can benefit from that expertise. It is seen as a benefit not a conflict that I have a foot in each door. However, I am no where near procurement nor procurement decisions. If anything joining the military makes it harder for me at Dragos to be an advocate to the government for our products and services, not easier. There are very strict ethics rules and I am far from the first to have to walk that line. My unit is aware and makes sure that I’m no where near anything that could be off nor have the perception of being off. My focus is on serving my country and community. For any competitors that want to talk trash (I only bring this up, because it’s already started) I invite them to join as well and can point them in the direction of a recruiter.

Even though there is no “national strategy” there are a lot of people working on OT cybersecurity across the government, what’s your thoughts?

Though I expect the 91st Battalion to lead the charge it’ll be through showcasing our capabilities and partnering with everyone. There are amazing people and teams across the government and I expect to pull them all in. It doesn’t matter ultimately what team or government agency “leads” so long as the work gets done. We’re going to use the 91st to plant the OT cyber flag strong and high – but all are welcome and I’m eager to learn, gain help from, and seek support from all the other amazing teams out there as well. This is a rallying cry not a takeover.

What is the time commitment for the Guard?

On the surface it’s roughly 49 days a year. 1 weekend a month 2 weeks a year is what they advertise. That’s the minimum. You can, I will, be doing more. But it’s incredibly flexible and the minimum is still amazingly impactful. It is something that can fit into most people’s schedules and provide an avenue for service.

How do I join?

While my path was a bit different the easiest is GoArmy.com and getting in touch with a unit in your state or recruiter. You are not bound to serve in your state (I don’t live in Virginia) but you need to find a unit that matches your expertise and desires – one almost certainly exists – and yes they’re hiring.

How has the current political landscape weighed into your decision?

It hasn’t. I started this process in the last Administration not knowing who was going to be President in 2025 nor caring. The military at its best is a truly apolitical organization. I have and remain apolitical and believe the military, especially now, needs leaders at all levels to focus on the mission and protecting our communities and to stay out of the politics. If anything the more divisive politics get the more excited I am to serve and hopefully give an example as well as protection to others to do the same apolitically.

Haven’t you thought of $X?

Yes probably. The FAQ cannot answer everything. The rumor mill in OT/ICS cybersecurity is often small and vicious. And the larger community is amazing and cares. The reality is I didn’t come to this decision lightly and I left the “blue years” over a decade ago. I have had time to think through all of this and while I’m sure there’s something that’ll surprise me I’ve come to this decision with a lot of thought and care. I appreciate people that will want to reach out and tell me what I’m doing wrong but at the risk of sounding arrogant – I’ve got it covered.